The Love of Money and the Cost of Terror: Official Development Assistance and Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula

By Hannah Pennington

This article appeared in CJFP's Winter 2024 publication.

Abstract

This research examines how Official Development Assistance (ODA) increases Al- Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) terrorism in Yemen from 2010 to 2020. This project adds to the discourse about how foreign aid and development assistance create the conditions of terrorism. The project utilized statistics from the Global Terrorism Database and World Bank in the descriptive analysis, negative binomial regression, and comparative analysis. Specifically, this research uses the net ODA received (current US dollars), net ODA received per capita (current US dollars), AQAP attacks, armed assaults, bombings, government targets, military targets, and police targets as variables for this analysis. This research argues ODA increased extremist activity in Yemen from 2010 to 2020. In addition, it argues the specific contribution of ODA increased AQAP targets and minimally impacted AQAP attacks and tactics. Therefore, this research project calls for American policymakers and diplomats to shift from using ODA as a counterterrorism measure.

Introduction

On 11 September 2001, Al-Qaeda murdered close to 3,000 people by hijacking four planes, two into the World Trade Center, one toward the Pentagon, and one derailed into a field in Pennsylvania. Although I was a mere infant, this event completely changed the world around me. Little did I know how much this event would change the trajectory of my family and friends’ lives. Shortly thereafter, the War on Terror began, and the United States invaded Iraq for a second time. The controversy over the justification of the invasion picked up speed and encapsulated the news. Families and friends sent their loved ones to join the fight, only for some to come home internally scarred, physically debilitated, or draped under our nation’s flag. As the media continued their tirade over US actions in the War on Terror, little attention was paid to the cost of freedom of those who gave their lives. While the War on Terror wraps up, I question whether counterterrorism tactics have the desired effect and at what cost.

Foreign influence in domestic affairs increases the likelihood of terrorists taking up arms due to the sentiments surrounding the history of colonialism. One example of foreign influence in domestic affairs is development assistance--the allocation of foreign money to aid socioeconomic issues. The Agence Française de Développement, in “Development aid: What’s it all about?” (n.d.) states Official Development Assistance (ODA) is financial assistance from well-off countries or international entities to improve living conditions in struggling countries.[1] In addition, ODA is a loan or grant aimed at improving water quality, health care, education, living conditions, and more. In this case, well-off countries contribute toward ODA to fix various socioeconomic and political issues in Yemen, serving as a form of foreign interference. Although ODA provides humanitarian aid, develops long-term projects, and helps the Yemeni government, it can also give reasons for AQAP to take up arms due to foreign interference.

Consequently, the international community’s contribution of ODA toward the Yemeni government and military entities from 2010 to 2020 increased terrorist attacks, primarily impacting AQAP targets, and minimally influencing AQAP attacks and tactics.[1] On a big scale, the allocation of ODA increased terrorist attacks in Yemen. However, regarding AQAP, the contribution of ODA increased the number of targets the following year and marginally impacted the number of attacks and tactics. The literature review covers how foreign aid increases terrorism. In the research design, the project utilizes statistics from the World Bank and Global Terrorism Database in descriptive analysis, negative binomial regression, and comparative analysis. Therefore, this research breaks down foreign interference via ODA in the descriptive analysis, how ODA increases terrorism in Yemen in the regression, and how ODA impacts AQAP operations in the comparative analysis section.

Literature Review

Scholars discover the United States contributes foreign aid if the country contains a security threat to the United States. If the country has a high number of anti-American terrorist groups, the United States assists them with foreign assistance in hopes of eradicating the security threat. Andrew Boutton and David B. Carter, find the relationship between terrorism and foreign aid is conditional on whether the country contains terrorist groups which serve as a security threat to the US.[2] Besides determining whether the country receives foreign aid, Boutton and Carter discover security threats determine how much aid the country receives as well. “In contrast, the presence of terrorism targeted at non-US interests, even if it targets formal allies of the United States, is generally unrelated to US aid allocation” (Boutton and Carter 2013). In this case, Yemen receives foreign aid because the country houses Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. The United States sends foreign aid to Yemen to eradicate the AQAP and protect citizens. Therefore, examining the allocation of ODA from international actors and the United States extends the scholars’ debate.

Therefore, this research project answers the academics’ request for a more detailed understanding by focusing on how the allocation of ODA increases AQAP operations. In addition, this project addresses the limitations of prior research by analyzing the effectiveness of ODA as a counterterrorism measure. Due to the call for more research and the limitations, this research contributes to a stronger understanding of the relationship between ODA and terrorism for United States politicians to implement effective counterterrorism policies. Thus, comparing AQAP attacks, tactics, and targets with changes in ODA will aid future counterterrorism measures by breaking down the consequences of foreign interventions in Yemen. Researching ODA and AQAP operations from 2010 to 2020 will aid future counterterrorism measures through a deeper political, social, and economic understanding of conditions that foster terrorism.

Research Design

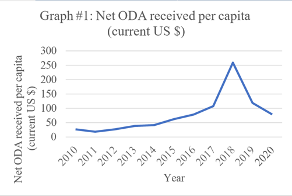

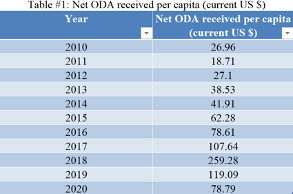

This research utilizes descriptive analysis by employing the World Bank database for statistics on net Official Development Assistance received (current US $) and net ODA received per capita (current US $) in Yemen. For example, the World Bank in the “Metadata Glossary” (n.d.) defines net Official Development Assistance as “disbursements of loans made on concessional terms (net of repayments of principal) and grants by official agencies of the members of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC), by multilateral institutions, and by non-DAC countries to promote economic development and welfare in countries and territories in the DAC list of ODA recipients.” Similarly, the net ODA per capita is the net repayment of principal made to DAC aid recipients and is calculated by dividing the net ODA received by the midyear population[3]. In order to implement these variables into a descriptive analysis, I created a table with the existing statistics on Official Development Assistance from the World Bank and generated a line graph with plots for ODA. Graphs from the descriptive statistics visualize the change in ODA in Yemen from 2010 to 2020 and later help comparatively analyze the relationship between ODA and increasing AQAP terrorist activities. Although descriptive analysis does not serve as the primary method of analysis due to the sole focus on the statistics from the World Bank, descriptive statistics uncover patterns in ODA and foreign influence in domestic affairs via graphs and tables.

In addition to descriptive analysis, this project utilizes statistics on terrorist operations and tactics from the Global Terrorism Database (GTD) to employ comparative analysis. First, I collected statistics on AQAP attacks, targets, and types of attacks from 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2020 in Yemen by filtering all the information by year, country, location, and perpetrator. Then, I grouped the statistics into groups based on conflict type, such as the outbreak of the Arab Spring (2010 to 2013), the Yemeni Civil War (2014-2016), and the ongoing conflict (2017- 2020). Within each group, I generated a data table to convey the causation between ODA and AQAP terrorism. Employing comparative analysis demonstrates how ODA increases AQAP terrorism through tables and graphs for each timeframe. Further, this research utilizes two overall comparative graphs as well as individual tables for each subgroup to visualize the change in terrorism and ODA throughout the decade.

Further, this research uses negative binomial regression, with the direction of a thesis mentor in organizing Global Terrorism Database statistics on all terrorism events from 2010 to 2020. As a reference point on the global scale, negative binomial regression predicts the probability of terrorism attacks in Yemen from 2010 to 2020. Specifically, negative binomial regression generates the statistical probability of terrorist attacks, locations targeted, and tactics used from 2010 to 2020 and determines the mathematical likelihood of increasing ODA. First, I downloaded a table from the Global Terrorism Database and filtered the table so only information on terrorist events, targets, locations, and tactics from 2010 to 2020 remained. [4]Then, with the tutelage of a thesis mentor, we employed negative binomial regression within STATA to calculate the probability of terrorist attacks, locations, target types, and tactics used within this timeline. Further, this mode of analysis demonstrates the statistical significance of global terrorism probability beyond regular correlation. Thus, the negative binomial regression statistically demonstrates ODA is a positive predictor of terrorist attacks in Yemen.

Analysis

Global Impact of Development Assistance

In this case, Official Development Assistance is a form of monetary contribution to Yemen from any country or organization, intending to assist Yemen with humanitarian, economic, and conflict issues. Specifically, development assistance, referred to as development aid or ODA, addresses human rights violations, poor education, and more within a specific country through financial assistance. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, in “Aid at a Glance” (2023), states the top ten donors of Gross Official Development Assistance for Yemen from 2019 to 2020 were Saudi Arabia, the United States, the International Development Association, the United Kingdom, Germany, the United Arab Emirates, the European Union, Japan, the Central Emergency Response Fund, and Sweden.

From 2019 to 2020, 76.39 percent of ODA went toward humanitarian aid and 9.84 percent went toward social infrastructure, such as improving living, education, and health conditions [5]ODA, in the form of monetary donations, improves Yemen's economic, social, and political well-being. Therefore, a form of international interference in domestic affairs is the significant monetary allocation of ODA toward Yemeni issues and conflicts.

The United States is the main trendsetter of Official Development Assistance in Yemen because the US relaunched development assistance in 2017, subsequently creating a spike in aid. The United States relaunched aid in 2017 in response to the designation of the Yemen Crisis.

From May to November 2017, humanitarian agencies and international actors designated the Yemen crisis as one of the worst humanitarian emergencies in the world[6]. The United States relaunched ODA in 2017 to help with humanitarian efforts, such as food shortages, cholera outbreaks, poverty levels, and education levels[7]. In addition, the US created a significant spike in net ODA per capita (current US $) in 2018, increasing from 107.64 in 2017 to 259.28 (see Table #1 and Graph #1). Foreign interference increased terrorism: however, the Yemeni government received more support because the United States resurrected ODA to Yemen. The Yemeni government received more ODA and increased the specific allocation of aid in determining AQAP terrorist attack targets for the subsequent year.

Despite the specific aim of development assistance in Yemen, the questionable intention of American aid consists of the competition over the allocation of military and humanitarian assistance and the emergence of AQAP. Such questionable intentions include whether the United States should allocate more ODA toward military or humanitarian relief and whether the US should designate aid toward fighting AQAP or improving Yemeni wellbeing. The Human Rights Watch, in “World Report 2011: Yemen” (2023), states the United States doubled military assistance to Yemen to $150 million in 2010. The same year, the US allotted less money towards humanitarian assistance, only $110 million, in comparison to military assistance[8]. At the same time, the AQAP became designated as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) on 19 January 2010[9]. Although ODA aims to help improve socioeconomic conditions, the United States uses ODA for political and military control through counterterrorism campaigns in the War on Terror. Hence, the true intentions of political and military control differ from the façade of sending money to Yemen to improve humanitarian issues.

Statistical Significance of Development Assistance and Terrorism

States promise to use development assistance towards counterterrorism but keep the security threat alive to continue pocketing the money. The Yemeni state relies on development assistance to function, inherently keeping the threat of militant groups, such as AQAP, alive to keep the country afloat. Andrew Boutton, in “Of Terrorism and Revenue: why foreign aid exacerbates terrorism in personalist regimes” (2019), states:

Yemen is a prototypical personalist dictatorship, heavily reliant on patronage to maintain a coalition of competing political factions, and is also home to a branch of al-Qaeda.

Saleh knew that the US relied upon him, and felt that his importance was conditional on not ending the terrorist threat. US officials’ credulity (e.g. Wikileaks, 2010) and the informational asymmetry between the two countries allowed Saleh to present himself publicly as a reliable, if imperfect, counterterrorism ally, while covertly inflaming the problem (p.378).

The specific contribution of ODA to Yemen increased terrorism because the government needs both to financially stay afloat. In this case, the government sends ODA to eradicate a security threat; however, the ODA increased terrorism because of the cyclic effect of the reliance of ODA on terrorism.

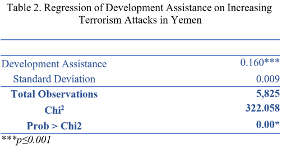

Development Assistance is statistically significant and a positive predictor of terrorist attacks in Yemen from 2010 to 2020. The probability of chi-squared and marginal prediction in the negative binomial regression determines development assistance as a factor of terrorism. In Table #2, 5825 terrorist attacks occurred in Yemen from 2010 to 2020. The marginal prediction indicates one unit of change in development assistance designates a 1.174 change in the subsequent number of attacks. The probability of chi-squared is 0.00 and under 0.05, indicating statistical significance between development assistance and terrorism attacks in Yemen from 2010 to 2020 (see Table #2). As a reference, the negative binomial regression states the statistical significance of terrorism to quantitatively prove the relationship with development assistance in Yemen. In addition, the regression demonstrates the existence of a positive relationship between ODA and terrorism in Yemen beyond correlation through statistical models. Although this regression serves as an overall statistical link between all Yemeni terrorism and ODA, the comparative analysis discovers ODA allocation quantitatively increased AQAP target evolution.

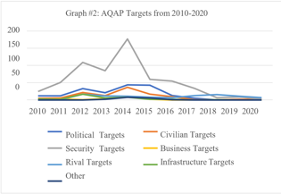

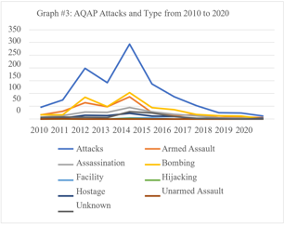

AQAP attacks and ODA throughout the Arab Spring

AQAP mainly carried out armed assaults and bombings on political and security targets throughout the decade. Political targets include government attacks and security targets include attacks on the military and police. The AQAP carried out these tactics and targets due to convenience and the context of the various conflicts. For instance, in Graphs #2 and #3, AQAP executes more armed assaults and bombings on political and security entities than other tactics and targets. For example, on May 8th, 2020, the AQAP killed two pro-government Yemeni soldiers by bombing a security checkpoint in the Al Wade’s district[10]. Understanding the frequency of AQAP targets throughout the decade breaks down the relationship with ODA because of the context of the various conflicts and the convenience of attacks. Thus, the allocation of ODA impacts who the AQAP targets and not necessarily how AQAP carries out attacks.

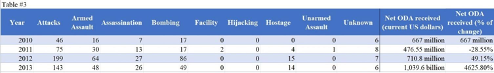

As the Arab Spring broke out in 2011, ODA decreased, and the number of AQAP attacks increased in the subsequent year. This trend demonstrates an inverse relationship between ODA and AQAP attacks. In Table #3, the net ODA received (current US dollars) decreased by 28.55 percent from 2011 to 2012. AQAP attacks increased from 75 in 2011 to 199 in 2012 (see Table #3). The AQAP increased “its hitting probability, causing heavy casualties and enormous economic losses”[11]. The decrease in ODA and increase in AQAP attacks counter the thesis because ODA did not increase AQAP attacks. Although the amount of ODA did not increase the number of AQAP attacks the following year, the financial allocation toward the Yemeni government or military influences the target of those operations.

Furthermore, ODA decreased, and the number of AQAP tactics increased as the Arab Spring broke out. Specifically, the net ODA received (current US $) decreased from 2010 to 2011, and the amount of AQAP-executed armed assaults and bombings increased the following year. For example, in Table #3, the net ODA received (current US dollars) for 2011 decreased by 28.55 percent, from $667.8 million to $476.5 million. AQAP increased the number of armed assaults from 30 in 2011 to 64 in 2012 and increased bombings from 17 in 2011 to 86 in 2012 (see Graph #3). On May 8th, 2012, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) discovered and prevented an AQAP plan to bomb a US-bound airliner from Yemen with an Improvised Explosive Device (IED)[12]. Although ODA decreased as AQAP tactics increased, the United States’ discovery of an AQAP plan caused the increase in AQAP tactics. The AQAP increased tactics in retaliation to the United States discovering the plan to bomb an airliner due to the sentiments attached to international interference.

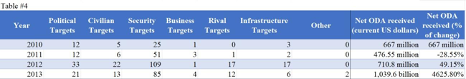

As the net ODA received (current US $) decreased from 2010-2012, AQAP targets increased. Primarily, AQAP attacks on political and security personnel increased. For example, as net ODA decreased, AQAP attacks on political targets increased from 12 to 33 and security targets increased from 51 to 109 (see Table #4). The United States Department of State in “Foreign Assistance” (n.d.) states the United States gave Yemen $13.653 million toward the military and $21.03 million toward the government sector in 2010. The following year the United States allocated $21.757 million to the Yemeni military and $22.45 million to the government sector[13]. Financial support through the allocation of ODA increased the likelihood of targets of AQAP terrorist attacks. Therefore, the specific allocation of ODA toward the Yemeni military and government increased AQAP attacks on military and government entities.

From 2014 to 2016, ODA increased as the number of AQAP tactics decreased. Specifically, the net ODA received (current US $) increased as AQAP armed assaults and bombings decreased. For example, according to Table #5, the net ODA received from 2014 to 2015 increased by 52.7 percent. The AQAP carried out 18 armed assaults and 37 bombings in 2016, decreasing from 25 armed assaults and 45 bombings the year prior (see Table #5). Despite the decrease in tactics, “the new issue of AQAP's Inspire magazine, released on December 24, featured instructions on how to build what AQAP called a hidden bomb from easily purchasable materials,” and the issue included directions on how to evade airport security (Cruickshank et al. 2015). In this case, the increase in AQAP tactics correlates with the outbreak of the Yemeni Civil War because the increase in ODA did not cause a decrease in AQAP tactics. Thus, ODA does not cause a decrease in AQAP tactics because ODA increased.

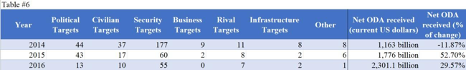

From 2014 to 2016, as the allocation of ODA toward the military and government decreased, AQAP targets decreased. Specifically, AQAP attacked fewer political and security entities due to the decrease in the allocation of ODA. For example, in Table #6, political attacks decreased from 43 in 2015 to 13 in 2016 and security attacks decreased from 60 in 2015 to 55 in 2016. In addition, the United States contributed $4.393 million toward governance and $241 thousand toward the military in 2015, decreasing significantly from $27.38 million toward the government and $21.366 million toward the military in 2014[14]. The number of AQAP attacks on political and security entities decreased due to the specific allocation of aid toward the military and government. Therefore, the specific allocation of assistance toward various entities determined the targets of AQAP attacks for the subsequent year.

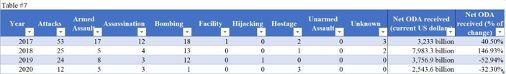

As the Yemeni Civil War persisted from 2017 to 2020, ODA increased, and AQAP attacks barely changed. AQAP attacks decreased by one unit over a year, even though ODA exponentially grew. For instance, in Table #7, the net ODA received (current US $) increased by 146.93 percent, from $3.233 billion to $7.983 billion. In the subsequent years, attacks decreased from 25 in 2018 to 24 in 2019 (see Table #7). Even though AQAP attacks decreased as ODA increased in this scenario, one unit of change in attacks is not substantial enough to quantitatively demonstrate ODA increased AQAP attacks. The allocation of ODA barely affects AQAP attacks in this scenario due to the increase in ODA and the minuscule change in AQAP attacks.

As ODA increased, AQAP bombings decreased, and armed assaults increased. ODA impacted tactics differently because armed assaults increased, and bombings negligibly changed from 2017 to 2020. In Table #7, as ODA increased, bombings decreased from 13 in 2018 to 12 in 2019. In comparison, the number of AQAP armed assaults increased from five in 2018 to eight in 2019 (see Table #7). The United States Department of State in the Country Reports on Terrorism 2018 (2019) states on June 14th, the AQAP targeted “UAE- backed forces in al-Wada’a district in Abyan governorate.” Even though bombings and armed assaults decreased, one unit of change is not substantial enough to prove the relationship between ODA and AQAP tactics. Therefore, ODA minorly impacts AQAP tactics from 2017 to 2020 due to the minuscule change in armed assaults and bombings.

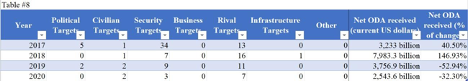

In addition, as ODA increased, AQAP increased attacks on political and security entities because of the specific contribution of ODA to the government and military. However, rival targets decreased as ODA increased. In Table #8, AQAP carried out zero political attacks, seven security attacks, and 16 rival attacks in 2018, and two political attacks, 9 security attacks, and 11 rival attacks in 2019. The United States Department of State in “Foreign Assistance” (n.d.) states the US allocated $250,000 in 2017 and $5.4 million in 2018 toward the military. In addition, the US increased ODA allocation toward the government from $8.212 million in 2017 to $24.08 million in 2018[15]. The contribution of ODA increased AQAP security and political targets; however, this pattern does not hold for rival targets due to the decrease in rival targets. Thus, the allocation of aid toward government and military entities increased the likelihood of AQAP terrorist attack targets.

Discussion

Despite the difference between Karl Marx’s old conflict theory on the class divide and the conflicts in Yemen, financial assistance sparks conflict with terrorist organizations and supports a more modern interpretation of conflict theory. In addition, foreign nations inherently finance the conflict in Yemen through the specific allocation of ODA. For instance, ODA is statistically significant and a positive predictor of terrorist attacks in Yemen (see Table #2). The specific allocation of financial assistance through ODA increased AQAP targets throughout these stages of unrest. Analyzing how ODA is a positive predictor of terrorism attacks and how the allocation of ODA increases AQAP targets, adds to the discourse of the modernization of conflict theory because it looks at other factors of conflict besides class, such as financial assistance.

The United States should stop relying on ODA as a counterterrorism measure because ODA increased terrorism. In addition, it increases AQAP terrorist attack targets, calling for the US to stop claiming ODA as effective. For example, Boutton and Carter (2013) discover the US contributes aid if the country contains a security threat. However, Yemen relies on the ODA to function but keeps the threat of the AQAP alive to continue pocketing the aid. ODA is statistically significant and a positive predictor of terrorist attacks (see Table #2). Therefore, the switch away from using ODA as a counterterrorism measure would decrease the number of terrorist attacks and save lives.

By halting the usage of ODA as a counterterrorism measure, US politicians should redirect the money toward Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) aimed at making sure the Yemeni population gets food, water, access to schooling, job assistance, housing, and more throughout the crisis. In doing so, the financial assistance through previous ODA gets to the people that need it, instead of the money trickling down through corrupt government bureaucracy and terrorist organizations. This process is an indirect, yet subtle way to help the population and avoid the sentiments surrounding direct foreign intervention in domestic affairs. Thus, US politicians should redirect the financial assistance of ODA toward NGOs because the money will address the conditions of the Yemen Crisis, end up where directed, and have a longer-lasting impact on the community instead of in the hands of corrupt politicians and terrorists.

Conclusion

Thus, the allocation of ODA to Yemen from 2010 to 2020 increased AQAP attacks on political and security targets; however, minimally influenced AQAP attacks and tactics. Despite the fluctuation in AQAP terrorism, ODA increased overall Yemeni terrorist attacks. This research discovers an inverse relationship between ODA and AQAP terrorism, as well as a positive relationship between all Yemeni terrorism and ODA. Even though the relationship between ODA and AQAP terrorism is an inverse relationship and not a positive linear relationship, this project finds a clear connection between the two. The United States should understand what increases terrorism and should stop implementing ODA as a counterterrorism measure because ODA increases terrorism. In addition, US politicians should care about this research because it could help decrease terrorist attacks and save lives.

Bibliography

Abdo, M. “Roadside bombing hits security checkpoint in southern Yemen, 2 killed.” Xinhua General News Service. May 8, 2020. https://advance.lexis.com

“Aid at a glance charts.” Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2023) https://www.oecd.org/countries/yemen/aid-at-a-glance.htm.

“Al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).” n.d. Global Terrorism Database (2022). https://www.start.umd.edu.

“Al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).” n.d. Counter Terrorism Guide. National Counterterrorism Center. https://www.dni.gov/nctc/groups/aqap.html

Boutton, Andrew. “Of terrorism and revenue: Why foreign aid exacerbates terrorism in personalist regimes.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 36, no. 4 (2019): 359–384. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26959449

Boutton, Andrew and David B. Carter. “Fair-Weather Allies? Terrorism and the Allocation of US Foreign Aid.” The Journal of Conflict Resolution 58, no. 7 (2014): 1144–1173. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24545618

“Country Reports on Terrorism 2018.” U.S. Department of State (2019). https://www.state.gov/reports/country-reports-on-terrorism-2018/#Yemen

Curran, Cody. “AQAP and suspected AQAP attacks in Yemen tracker 2010, 2011, and 2012.” Critical Threats (2010). https://www.criticalthreats.org.

Cruickshank, Paul, Pamela Brown and Rene Marsh. “Heightened security checks coming to U.S. airports after AQAP calls for lone wolf plane bombers.” CNN. January 14, 2015. https://advance-lexis-com.www2.lib.ku.edu/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:5F2V-PHP1- DY60-M4FN-00000-00&context=1516831

“Development aid: What's it all about?” n.d. Agence Française de Développement. https://www.afd.fr/en/development-aid-whats-it-all-about

“Foreign Assistance.” n.d. United States Department of State. https://www.foreignassistance.gov/

“Metabank Glossary.” n.d. World Bank. https://databank.worldbank.org

Montgomery, Marcus. “A timeline of the Yemen crisis, from the 1990s to the present.” Arab Center Washington DC. February 19, 2021. https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/a-timeline-of-the-yemen-crisis-from-the-1990s-to-the-present/

“Terrorist events in Yemen.” Global Terrorism Database. https://www.start.umd.edu.[4]

“World Development Indicators.” n.d. World Bank. https://databank.worldbank.org

“World Report 2011: Yemen.” Human Rights Watch. January 23, 2023. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2011/country-chapters/yemen

“Yearender: Yemen-based al-Qaida bring about renewed threats in 2010.” Xinhua General News. December 23, 2010. https://advance.lexis.com[5]

“Yemen.” U.S. Agency for International Development. December 12, 2022. https://www.usaid.gov/yemen

[1] “Development aid: What's it all about?” n.d. Agence Française de Développement. https://www.afd.fr/en/development-aid-whats-it-all-about

[2] Andrew Boutton and David B. Carter, “Fair-Weather Allies? Terrorism and the Allocation of US Foreign Aid.” The Journal of Conflict Resolution 58, no. 7 (2014): 1144–1173. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24545618

[3] “Metabank Glossary.” n.d. World Bank. https://databank.worldbank.org

[4] “Terrorist events in Yemen.” 2022. Global Terrorism Database. https://www.start.umd.edu.

[5] “Aid at a glance charts” Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2023) https://www.oecd.org/countries/yemen/aid-at-a-glance.htm

[6] Marcus Montgomery, “A timeline of the Yemen crisis, from the 1990s to the present,” Arab Center Washington DC. February 19, 2021. https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/a-timeline-of-the-yemen-crisis-from-the-1990s-to-the-present/

[7] “Yemen”, U.S. Agency for International Development (2022), https://www.usaid.gov/yemen

[8] “World Report 2011: Yemen,” Human Rights Watch. January 23, 2023. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2011/country-chapters/yemen

[9] “Al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP),” n.d. National Counterterrorism Center. https://www.dni.gov/nctc/groups/aqap.html

[10] M. Abdo, “Roadside bombing hits security checkpoint in southern Yemen, 2 killed.” Xinhua General News Service, May 8, 2020. https://advance.lexis.com

[11] Xinhua General News, December 23, 2010. https://advance.lexis.com

“Yemen,” U.S. Agency for International Development, December 12, 2022. https://www.usaid.gov/yemen

[12] Cody Curran, “AQAP and suspected AQAP attacks in Yemen tracker 2010, 2011, and 2012” Critical Threats (2010). https://www.criticalthreats.org.

[13] “Foreign Assistance,” n.d. United States Department of State. https://www.foreignassistance.gov/

[14] “Foreign Assistance” United States Department of State.

[15] “Foreign Assistance”, United States Department of State.